Little Women: Episodes 1-2

by alathe

From the delightfully unsettling opening credits, to the beautifully dark twist it puts on Louisa May Alcott’s novel, Little Women’s first two episodes are a treat from start to finish. Three sisters face a brutal corporate world that seems designed to make them fail — and a conspiracy that threatens to swallow them whole.

EPISODES 1-2 WEECAP

We begin in the humble Oh family flat, where OH IN-JOO (Kim Go-eun) and OH IN-KYUNG (Nam Ji-hyun) prepare to celebrate the birthday of their younger sister, OH IN-HYE (Park Ji-hoo). It’s markedly different to their birthdays of yore: for one thing, they can afford cake, rather than a plate of boiled eggs with a candle. Much like the little women of Louisa May Alcott’s novel, our protagonists grew up with nary two coins to rub together. However, their mother, AHN HEE-YEON (Park Ji-young) is a dark parody of Alcott’s loving Marmee: blusteringly selfish, a pall is cast the minute she enters the room.

Still, there’s room for birthday cheer. In-joo and In-kyung have rustled together enough money to send In-hye on a trip to Europe — courtesy of the fancy arts school she attends on scholarship. In-hye considers it too good to be true.

Sadly, she’s not wrong. Hee-yeon’s already kicking up a stink about being unable to visit her husband, whose gambling debts sent them spiraling into poverty. Sure enough, next morning, both Hee-yeon and the envelope of cash have vanished, leaving a sanctimonious note and a heap of homemade kimchi.

Despite In-hye’s quiet teenage resignation, the elder sisters are determined to raise more money. Easier said than done. In-joo receives nothing but a delicate sneer of disdain when she begs her boss for an advance. Surrounded as she is by cliquey co-workers with the same flashy smiles and flashier family connections, our heroine is isolated — but not quite alone.

Granted, her fellow office outcast, orchid enthusiast JIN HWA-YOUNG (Chu Ja-hyun), insists they keep their friendship a secret. For all that they’re each other’s refuge from endless corporate snobbery, openly lunching together would only make the others shun them more. Still, she’s happy to lend In-joo the 1.25 million won she needs.

Meanwhile, In-kyung has her own workplace demons to face. It’s hard at the best of times to be a reporter covering harrowing stories of poverty. It’s harder when you can’t stop crying on camera. In-kyung struggles to make it through the day without heading to the bathroom for a swig of… probably not mouthwash.

Much as Hwa-young insists on not lunching with In-joo at work, this doesn’t prevent them from dining out — at a snazzy hilltop restaurant, where they can dress up and dream together. In-joo is adamant that her cheap pink skirt works fine, but her pride crumbles when her shoe heel snaps. Hwa-young, with gentleness belying her brittle workplace persona, helps spruce up her friend’s look, lending In-joo her own pair of expensive — yet comfortable! — Bruno Zumino heels.

As they laugh together over steak, Hwa-young shares a scheme. She’s patenting her accounting software Bookkeeper From the Future — a program she’s adamant will revolutionize the workplace, and consign their insufferable colleagues to the dustbin of history. Intrigued, In-joo signs the form.

Something’s a little off, though — for one thing, the wait staff recognize Hwa-young. Apparently, she came here with the company director, after working together late — rendering them the subject of scurrilous office rumors. Still, it gets stranger: In-joo encounters a woman wearing the same Bruno Zuminos. Turns out, it puts them in the same hyper-exclusive club: only three pairs are available in Korea.

That evening, In-kyung, after a fortifying gulp of definitely-not-mouthwash, meets with her estranged — and affluent — Great Aunt, OH HYE-SUK (Kim Mi-sook). She maintains steely perfect posture, as K-drama’s answer to Lady Bracknell expounds on how a gloomy male housekeeper is aesthetically preferable to a cheerful one. (I find this woman unironically delightful.)

Great Aunt Oh offers to pay for In-hye’s trip, in exchange for In-kyung visiting her weekly. This business thus concluded, she hustles In-kyung out the door — ensuring she bumps into her childhood friend: HA JONG-HO (Kang Hoon).

From In-kyung’s reaction, this isn’t the first time she’s thrown them together — and what better way to prove that familial affection still holds strong than meddling in your grandniece’s love life?

Later, In-joo presents In-hye with the money — only to be rebuffed in the flat manner of a teenager with something to prove. In-hye can’t stand her sisters suffering for her sake.

Besides, she’s nothing if not entrepreneurial: In-joo discovers she’s earning money from a classmate’s mother in exchange for painting with her daughter. In-hye is proud — In-joo, appalled. To her mind, it’s tantamount to begging: she’s insistent her sister will not be pitied.

Back at work, In-kyung has a new case — another tearjerker. Mayoral candidate PARK JAE-SANG (Eom Ki-joon) has issued a heartfelt apology to a man framed — and tortured — for espionage in 1987, on behalf of his father-in-law, who headed Defense Security Command at the time.

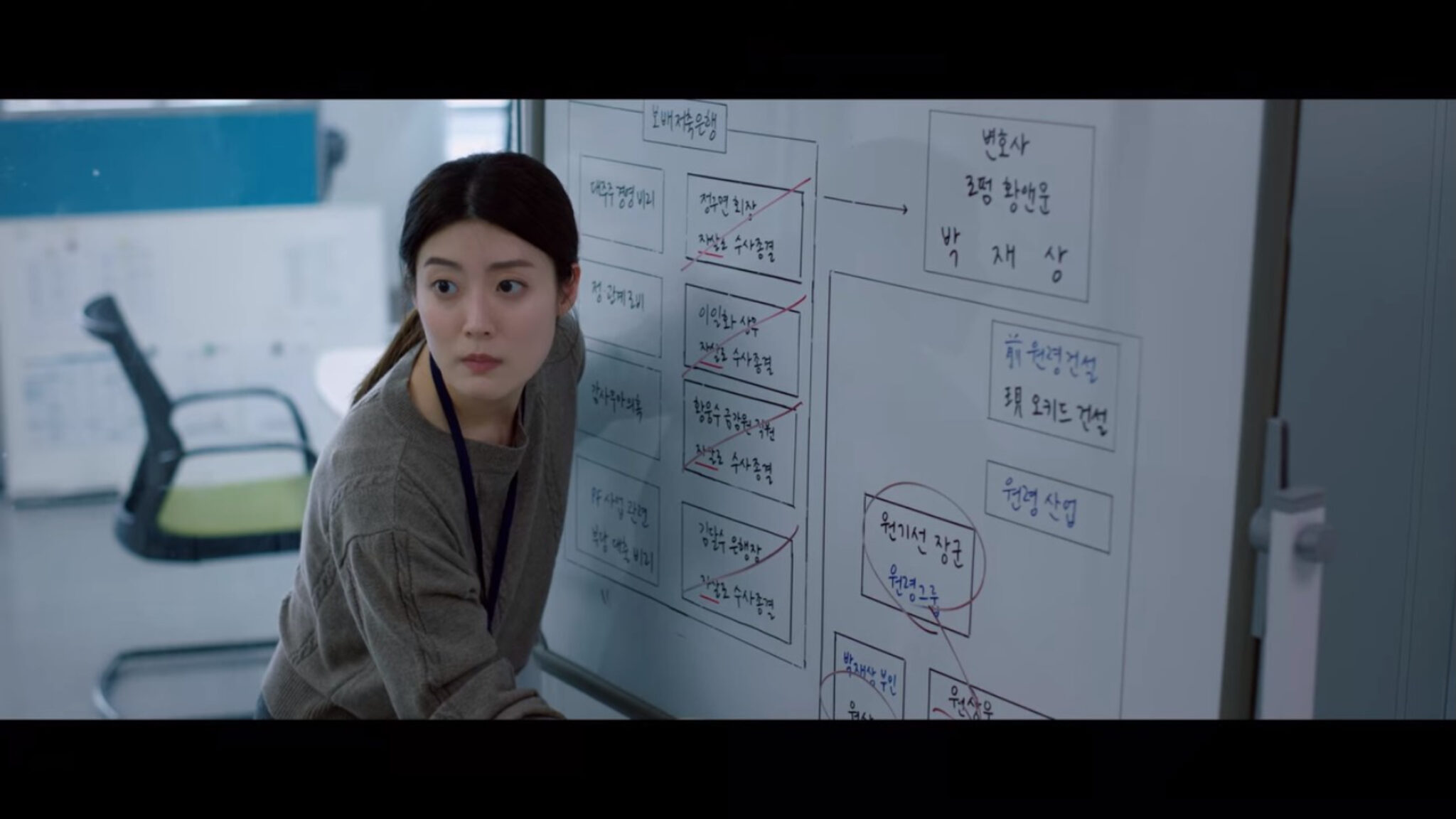

For once, our heroine’s eyes are dry: having followed the money, she isn’t fooled. The attorney-turned-politician once represented Bobae Savings Bank, who profited from the military regime. As she digs deeper, what she discovers stinks to high heaven: during the case, four defendants took their own lives. All were represented by Jae-sang. Furthermore, all left money unaccounted for — to the tune of 140 billion.

Hwa-young prepares to go overseas, leaving In-joo encyclopedic instructions on caring for her plants — which anyone who’s attempted to keep an orchid alive will recognize as optimistic. She’s sent some light reading, too: a dossier detailing the secrets of their office nemeses. Plus, yoga videos. In-joo must improve her posture!

Alas, it’s awkwardly mid-video that a friend of Hwa-young’s discovers In-joo: CHOI DO-IL (Wie Ha-joon), whose unflappable manner suggests he regularly encounters women on tables in a wobbly approximation of tree pose. Better still — he asks for her number, with a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it smile. He’s charming, and she’s charmed, but it’s only prudent to get ahead of the gossip. She tells him upfront: she’s a divorcee with only a two-year course in accounting under her belt. He’s superbly unconcerned — Hwa-young already told him about her fellow outcast.

Despite this hopeful beginning, things go abruptly awry for both sisters. At a charity launch, In-kyung confronts Jae-sang about the Bobae Savings deaths. She receives a bland smile and a noncommittal answer. Later, the gloves come off: Jae-sang ambushes her in the foyer, noting loudly that she’s crying. As In-kyung’s jealous colleague discreetly films them, he declares he can smell alcohol on her breath.

In-kyung returns to the office in disgrace; the video of Jae-sang shaming her has gone viral. In full view of her colleagues, her coworker checks her mouthwash bottle: it’s tequila.

Meanwhile, In-joo is rapidly growing concerned for Hwa-young, who ought to have returned by now. Visiting her flat, she finds no sign of its inhabitant: the rooms are strewn with boxes of clothes and accessories, but all is still.

Then, she catches sight of something gruesome in Hwa-young’s wardrobe: the flash of a red heel. Horrified, she moves forward, only to find a body dangling, half-hidden by clothes — with Hwa-young’s blue orchid tattoo on its ankle.

The aftermath of Hwa-young’s death is a blur of news. Disgusted by the shameless office gossip — her suicide note! Her plastic surgery! Her purported affair! — In-joo elects to quit in a blaze of outrageousness worthy of her friend. As whispers fly to and fro, she stands — and, to the awe of the staff, reads from Hwa-young’s dossier, revealing that her boss was sleeping with a subordinate.

It is precisely at this point that DIRECTOR SHIN (Oh Jung-se) strides into the room, Do-il at his heels. He requests a word with In-joo. It’s not to reprimand her — it’s worse. According to him, Hwa-young stole 70 billion won from their company, killing herself after he confronted her. He demands that In-joo reveal everything she knows. In-joo refuses to be intimidated: it’s clear he needs her help to recover his illegal slush fund. She slaps her resignation letter on the table.

Afterwards, she receives a call. It’s Jayz Yoga Studio, informing her that Hwa-young has transferred her membership to her. Utterly numb, she lets them give her the key to her friend’s locker. It takes her a while to muster the will to open it.

When she does, she finds a heavy duffel bag. Inside are yoga clothes. A pair of Bruno Zuminos. A note thanking her. And — two billion won in cash.

Elsewhere, In-kyung is subjected to the humiliating process of a disciplinary hearing. After admitting to her alcohol dependence before flanks of disapproving superiors, she receives a month’s suspension.

Telling a tribunal is one thing. Telling her sister is another. Over an annoyingly tasty bowl of their mother’s guilt-kimchi, In-kyung drops the news: she’s scared that, like their father, she’s an alcoholic. As both sisters choke back tears, In-joo insists that she’s nothing like their father, who was indecisive and weak; In-kyung is strong… and cold. It’s an unexpected blow. In fairness, In-joo is cycling through all five stages of grief in a single instant — landing squarely in angry acceptance: her sister must tell her when she needs help!

It’s a bold assertion from someone about to stuff her secret fortune into kimchi containers. But, In-joo’s not inclined to unburden her own troubles yet. For now, she’ll drown her emotions in binge-bought ice cream — all the while, questioning why someone with Hwa-young’s wealth would suddenly kill herself… and whether, indeed, she killed herself at all.

In-kyung receives a very different sort of support from Great Aunt Oh, who reckons a morning glass of whiskey never impeded her work as… erm, a medical professional. Yikes. In-kyung has no such illusions. She’s dependent on drink to dull her anxiety on camera. Moreover, journalism was never her dream — she still resents her great aunt for barring her from studying Economics. But family spats are a many-splendored thing: turns out, In-kyung was a dab hand at investment, spinning money by the millions throughout the course of her teens. In any case, here they are now: In-kyung biting her tongue over breakfast for the sake of a month’s pay; Great Aunt Oh, lonely enough to buy her company in the first place.

In-joo, meanwhile, armed with the new purpose of solving her friend’s murder, agrees to aid Director Kim in his less-than-legal investigation — in exchange for a cushy role at the International Orchid Society. She’s derailed somewhat by Director Kim’s disconcertingly personal commentary on her cheap shoes.

His own are dark green and immaculate. He advises she invest in better ones: after all, if we’ve learned anything from this show, it’s that shoes are a complex marker of social class. The cruelty of poverty is that it begets poverty; cheap shoes destroy your feet. Meanwhile, wealth accumulates wealth. Expensive shoes signify comfort, status — and aspiration.

Elsewhere, In-kyung gets serious about the pursuit of justice. Four years prior, she let go of a lead: the nephew of one of the dead defendants from the Bobae Savings case. Whilst she and Jong-ho reminisce over salad about her wild-child schooldays, she receives a call — now that she understands the extent of Jae-sang’s malevolence, her contact is willing to meet again.

In-joo’s own investigation is a little more personal. Under the watchful eye of Do-il — whose motives remain cloudy, but whose chivalry extends to guiding her away from underfoot cockroaches — she must scour the apartment of her dead friend. Hwa-young’s advice echoes in her ears: everything begins with money. It’s a matter of survival to understand the stories numbers tell. Eager to read between the numerical lines, In-joo begins cataloging the pricey clothes and handbags boxed up around the flat.

An eerie tale emerges. As a bookkeeper, Hwa-young always warned In-joo to mind appearances. Wear shabby clothes. Construct a persona free from suspicion.

A little digging reveals Hwa-young’s alter ego: Jin Mi-gyeong, glamorous Singaporean socialite, whose outfits were flawless, and whose fine dining habits were meticulously documented on social media. But her 70 billion won — or rather, 68 billion of it — remains unaccounted for.

It’s here that In-joo is interrupted by Director Shin — and the show reaches new heights of disturbing. Boxing In-joo against the wall, he whispers to her of money. Of luxury. He can give her both these things: and what’s more, he can eyeball her foot size to the nearest centimeter. It’s nastily intimate — In-joo is too frightened to push him away. However, after spotting a jar on Hwa-young’s wardrobe, he recoils of his own accord. It’s a blue orchid.

The flower’s sinister symbolism becomes clearer when In-kyung goes to meet her contact. She’s far too late: the wreckage of his car lies broken by the road. Nearby is his still-ringing phone — and another blue orchid.

In-joo still has shoes on her mind: she takes a trip to Bruno Zumino, where she encounters a helpful shop assistant with a familiarly handsome face. At least, to the viewer.

You know a show’s got confidence in its rock-solid cast when it can afford to throw away Song Joong-ki on a cameo. (Incidentally — check out his nametag…!) Anyway, Vincen— erm, that is, the shop assistant, confirms the buyer of Hwa-young’s exclusive heels: resident creep Director Shin.

In-joo takes a gamble on trust and reports her findings to Do-il. A deep dive into Hwa-young’s phone records reveals that she and Director Shin had planned a business trip to Switzerland. Before she left, Hwa-young reported the director for embezzlement, submitting evidence she’d collected over the years, ensuring he was held in Korea while she transferred the slush fund. But, Director Shin found out, and threatened that they’d both go down together. That she’d suffer the same fate as a woman named Yang Hyang-sook.

Turns out, Director Shin has a penchant for seducing vulnerable working-class women into white-collar crime sprees — only to leave them carrying the can when the police come sniffing. Hyang-sook was Hwa-young’s predecessor. Her story is chillingly similar, right down to the red heels she was wearing when she killed herself.

In-joo is determined to contact the police. However, justice proves an insufficient motivator for her money-minded compatriot. Do-il’s first concern is the missing 70 million — and, what’s more, he’s convinced that Hwa-young would agree. The two of them shared the same ethics — or, arguably, the same lack of them. Money is all that matters.

Meanwhile, In-kyung opens up to Jong-ho. She possesses empathy in spades. It goes into overdrive when she reports on a difficult news case. She can’t control her reaction — it’s why she drinks. All this to say that she knows Jae-sang is corrupt as they come: she can sense his complete lack of feeling. Jong-ho elects to test this empathetic superpower; he challenges her to guess what he feels for her. Alas, even a reporter’s sixth sense is no match for romantic obliviousness! In-kyung senses comfort, concern, and a certain amount of fluster… but, adorably, the sum of these parts eludes her.

She returns home to find that her sister has been trying Do-il’s money-is-all philosophy on for size. The table is a veritable smorgasbord of consumerist delights: creams, perfumes, and no less than five separate shades of scented lip gloss. None of it stops In-joo from collapsing into tears. Over a round of expensive ice cream, she confesses everything to In-kyung… everything, that is, besides the two billion won concealed in their bathroom.

They’re interrupted by an unexpected delivery. Director Shin has sent In-joo a pair of bright red heels.

Meanwhile, the third Oh sister is living her own double life. In-kyung turns to the TV in time to see the Grand Art Prize announced at In-hye’s prestigious school. The winning painting is a portrait of a seventeen-year-old girl in the style of Van Dyck, evoking old nobility. It’s the same portrait In-hye has been working on for weeks.

The winner is her schoolfriend, Park Hyo-rin — daughter of Park Jae-sang. In-hye may have consented to this scheme, but to judge by her furious pencil-scribbling, she’s far from happy.

Director Shin has taken a step too far this time. Unable to turn a blind eye like Do-il, In-joo leaves to confront him with all she’s learned. He is scathing: embezzlement is apparently just part and parcel of running a business.

Hyang-sook’s suicide was — complicated. But, the one who discovered her was Hwa-young, who immediately turned to him and asked for Hyang-sook’s old job. There was no affair; if anything, she had the upper hand over him.

As for him — he’s leaving for the prosecutor’s office. Deals will be made; he’ll get five years at most. The alternative is something that doesn’t bear thinking about… because, like it or not, he’s not the one at the top of the food chain. There’s someone he’s scared of, too.

With good reason. As In-joo watches him drive away, something’s fishy: his car brakes aren’t functional. The last thing Director Shin sees on his dashboard as he goes soaring off the side of the multi-story car park is a bright blue orchid.

This drama may well be my new obsession. With its intricate exploration of economic inequality, and its laser-focus psychological horror, Little Women is a show that knows exactly where it’s going. I’m in love with the lush, eerie world it creates — with one foot in dark realism, and the other in a sprawling almost-fantasy that refuses to apologize for itself. They truly did decide, if we want a sinister orchid garden in the middle of a corporate building, then by golly we’ll have one! I respect this immensely.

As for the characters — they’re already drawn so deftly. In-joo is a delight, with her impish hair-tossing and stubborn resolve. In-kyung has such intelligence and visible strength of will, despite her struggles. And In-hye remains an intriguing mystery; she’s so self-contained, but clearly has all number of secrets up her sleeve.

Meanwhile, the supporting characters are solid gold, from Do-il’s calm cynicism, to Great Aunt Oh’s well-guarded loneliness, to Director Shin’s delightfully creepy antics. Most of all, though, Chu Ja-hyun has unexpectedly stolen my soul as Hwa-young. Her relationship with In-joo is so compelling — my heart melted the moment she handed over her shoes. I’m calling it now: odds are about even that she faked her death. Or, maybe that’s just wishful thinking? Either way, bring on next episode — I’m already craving more!

RELATED POSTS

Little Women: Episodes 1-2

Source: Buzz Pinay Daily

0 Comments